Best known as ‘riccio’ (crisp curls) as the Veneto argot for the Latin crispus, both reflecting his part-African ancestry, Riccio was highly regarded in Renaissance Padua as a Humanist scholar and inventive creator of large ceremonial bronzes. Equally and lastingly cherished were Riccio’s smaller functional bronze desk appurtenances for private offices and libraries.

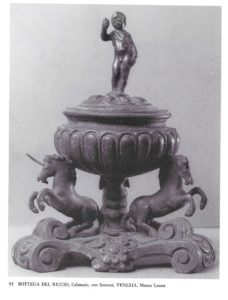

Employing and often mingling natural and very unnatural figurative, vegetative and animal grotesques in forays of fanciful wit, this inkwell deftly combined utilitarian function and Humanist antique ornament in sphynx supports for the wide deep bowl with rinceau surrounds, while the gadrooned lid is topped by a figure of Mars as a handle. The female sphynx supports and the rinceau fragments on the lid hark back to late Hellenic and hence Roman decor already revived in full by Riccio’s day; the gadrooned bowl was an heir to antiquity as a basic utilitarian form from the Renaissance on. Riccio used these and related Greco-Roman motifs on both formal ecclesiastic works and informal desk pieces. In that way, the quite immense Pascal Candelabrum in the Santo in Padua is graced with a lateral sphynx as architectural ornament, showing a fluid interchange of pagan motifs from ecclesiastic to domestic service. Then too, a structurally similar Riccio inkwell in the Museo Correr in Venice shows only generic internal modifications of motif to the inkwell here. Instead of Mars, the Correr example shows a more benign amoretto and instead of sphynxes is supported by equally fictive unicorns. Even the ornament of bowl and lid retain the gadroon and rinceau patterns, but in inverted placement.

N.b.: As relatively less finely chased and polished than many of the bronzes produced throughout the sixteenth century in Mantua, Padua and Venice for a luxury market, this inkwell is typical of surface traces of creation and cast that were often favored in northern Italian court circles.

Until recently, the only comprehensive monograph on Riccio remained Leo Planiscig’s Andrea Riccio, Vienna, 1927, most useful for its hundreds of illustrations with largely doubtful attributions. More recently, both the range of Riccio’s life, work and patronage, have been summarized in the excellent monograph by Denise Allen, Peta Motture et al, Andrea Riccio: Renaissance Master of Bronze, New York 2009, prepared for the eponymous exhibition at the Frick in 2008-9. Quite valuably, it includes a chapter (pp.81-96) by Richard E. Stone on Riccio’s materials and techniques of modelling and casting, particularly in anticipation of subsequent editions of these utile works of art.